Comprehensive Speed Development for Athletes by: Kevin Neeld

Speed is the most highly sought after physical quality in sports. It’s a key quality that separates athletes competing at different levels (i.e. higher levels of competitions have faster players), and a major determinant of what makes an elite athlete at a given level. As athletes and coaches attempt to improve speed, it’s important to understand which characteristics of faster athletes and which training strategies can positively impact speed.

“Everything is Speed Training”

Early in my career, I did an interview with Jim Snider (Metabolic Elite board member and then strength and conditioning coach for University of Wisconsin men’s and women’s hockey), where he said “everything is speed training.” He was right. While most people equate speed training with running sprints, the reality is that every aspect of a comprehensive training program can impact an athlete’s ability to develop and express speed.

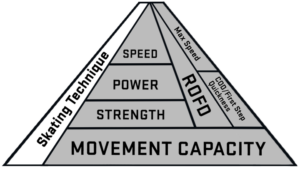

To help illustrate this concept, I developed the pyramid below as an overview of my model on speed development for hockey players.

There are a few important things to highlight here:

- Speed fundamentally comes down to stride length x stride rate. In all sports, certain positions are associated with faster movement, as a result of, among other things, optimizing stride length. For example, in hockey, higher caliber skaters are known to utilize a deeper skating position (i.e. increased hip, knee and ankle flexion) and longer stride lengths (i.e. increased hip abduction) while skating forward. Recognizing this, improving mobility and stability is not just an injury risk mitigation strategy, it has a direct impact on performance

- Technique can have a major impact on speed, but it’s also influenced by the athlete’s physical profile. For example, an athlete that lacks the mobility to get into specific positions will have a different stride signature than another athlete without mobility restrictions. Similarly, certain athletes have a genetic profile that is more “force-dominant” (e.g. “plough horses”), who may need to adopt deeper skating positions and longer stride times, opposed to more naturally explosive players (e.g. “race horses”), who may get away with higher skating positions during sub-maximal efforts, and have faster stride rates. Technique will need to adjust and be refined as athletes make progress in any physical quality.

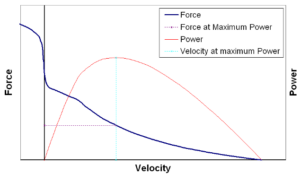

- Strength, power, and speed progress across the force-velocity continuum, with maximal strength work occurring more on the left (high force, low velocity), maximum power work in the middle (moderate force, moderate velocity), and maximum speed work on the right (low force, high velocity). High force dominant strategies are likely to have a larger impact on change of direction and first step quickness, and the more velocity dominant strategies will have a larger impact on maximum speed.

Image from Wikipedia.com

In the absence of a more detailed diagnostic process, athletes should understand that addressing EVERY quality in the pyramid will impact speed.

Speed Checklist

Athletes looking to better understand which area of the pyramid may be most limiting to their personal performance will benefit from going through testing. Here are a few examples of tests I’ve used in the past:

- Mobility: Ankle dorsiflexion, hip extension, hip adduction, hip abduction, hip external rotation, hip internal rotation, thoracic spine rotation

- Stability: Y-Balance Test

- Speed/Acceleration: 20-Yard Sprint, Wingate relative peak power

- Change of Direction: 5-10-5

- Power: Vertical jump, lateral bound

- Strength: 3-10 RM Trap bar deadlift, reverse Lunge

Ultimately, this will help you answer the below questions, which should drive the associated interventions:

| Diagnostic Question | Intervention |

| Can the player get into the right positions? | Unlocking ROM: Foam roll/lax ball, mobility, breathing, warming up

Creating ROM: Long duration holds, eccentric exercises to end range |

| Can they hold the right positions? | IsoHolds, Holds w/ Dynamic Challenges |

| Can they push out of deep positions? | Lower body strength work: push pattern emphasis, and horizontal plane emphasis |

| Can they explode out of deep positions? | Power Emphasis: Resisted and single-leg jumping

Speed Emphasis: Accelerations from kneeling starts |

| Can they create separation? | Power Emphasis: Continuous jumps

Speed Emphasis: Longer distance sprints, sprints from a flying start |

| Can they efficiently transition? | Transitional speed work emphasizing sport-specific patterns |

Equipped with this information, athletes can focus more effort on their specific limiting factor(s).

Capacity vs. Expression

It’s important to note here the difference between speed capacity and speed expression. Capacity refers to what an athlete could do; expression describes what a player does at any given moment. Ideally, the gap between these two is minimal, but here are a few main causes of diminished speed expression:

- Insufficient fuel or dehydration

- Soreness/fatigue from previous playing or training

- Poor sleep

- Illness

- Performance anxiety

- General sluggishness following a day off

- Excessive cognitive load (overload on processing/decision making)

Each of these will have an impact on a player’s ability to express their full speed, and to an extent they’re all modifiable. Synapsin, for example, is known to be extremely effective at improving focus and cognitive processing (i.e. decision making). Additionally, we’re seeing more examples of Synapsin also leading to improved speed of movement and better heart rate recovery, both of which speak to a potential mechanism of Synapsin improving the coordination of the nervous system (e.g. faster contraction/relaxation times).

Wrap Up

To maximize speed development, it’s critical to understand and address ALL of the major physical qualities that can impact speed. To maximize speed expression, it’s important to take a comprehensive look at lifestyle and tactical factors that impact daily readiness.